When I joined the Google Kubernetes Engine Node Team this Fall as an intern I didn’t know much about Kubernetes. Now, after three months of full time work on its internals, I still wouldn’t say I know much about Kubernetes. I figure probably Google was given the source code by aliens around 2012 and open-sourced it a year later (not sure on the exact timeline there).

Kubernetes is complicated. Not all hard problems have simple solutions, and Kubernetes addresses a lot of hard problems:

- Making containers talk to each other is hard

- Managing and observing deployed applications is hard

- Scheduling onto compute resources is hard

- Delivering secrets and config to running containers is hard

- Service discovery is hard

I mean, taken together, this stuff is so hard to do right that it keeps thousands upon thousands of people around the world in well-paid work. So, in a nutshell: if our goal is to make a single tool to handle all the hard parts of deploying software, it’s going to end up being pretty complicated. Complicated to the point that no single person can understand the whole picture (unless that person is Tim Hockin).

Hilarious to me was how specialized the roles have to be to make meaningful contributions to a project like Kubernetes. An engineer might be clueless about the Kubernetes networking model, but at the same time, the only person who understands how cluster-level metric aggregation works in detail. Another engineer might know the deep-down internals for the kubelet but wouldn’t know the kubectl commands that a cluster admin would consider basic knowledge. This is by necessity. I’d never worked on a codebase this large before and I’m sure the same holds true for other projects.

Note: the following sections were written in Winter 2019, in reflection

Experience

I spent the first month in that codebase lost without a home. There just wasn’t anywhere to grab onto. I remember spending an entire week vendoring OpenCensus into Kubernertes (for this PR). Diamond problems everywhere. I remember wanting to cry because I’d be trying to unravel some codepath and everything would just bottom out at an interface- I couldn’t figure out where actual state changes were happening (throwback to some dark, scarring Java experiences from days past).

I had zero experience with distributed systems at the time, and to be honest, I’d only learned what an environment variable was three months prior, so I was out of my depth. I was nervous that I’d ruin my shot at Google. I was nervous all the time. So I studied, let the project consume me. It got to the point where Kubernetes was the first thing I thought about when I woke up and the last thing before I went to bed. I might have developed a mild drinking habit at some point. In fact, I definitely did. I remember hopping on the G-bus at 7:45am after many a gin-filled evening.

A common frustration for new developers is onboarding to a new codebase. I’ve received mixed advice on approaching this: “Throw 0/0 somewhere and check out the stack trace” (!), “Start at main and work your way down” (please, point me in the direction of Kubernetes’ main). A wise mentor once told me the first place to look when confronted with a new codebase is the tests. Ok, that one kind of makes sense… we can look at what should be happening in digestible chunks, maybe understand the interface boundaries better. Except that this is terrible advice for understanding the Kubernetes codebase. To date I haven’t encountered a project with scarier test infrastructure (even the authors of Prow, I think, live in fear of what they have created). These kinds of tests, for instance, do not exist to onboard devs.

The answer I found for onboarding to a project like Kubernetes was to struggle through the docs. Especially these docs. If you’re a stranger to distributed systems like Kubernetes it could take a few days to absorb the concepts and that’s fine. Diving headlong into the codebase did not work for me here. What does etcd provide, why do we even need a special KV store? What components run on the masters and what runs on the workers? When a Pod gets scheduled what components notice the scheduling decision and react? You can’t write sensible code before having those mental models in place. I watched dozens of conference talks on the Kubernetes architecture during my first month at Google. I didn’t write much code until weeks into my 3-month internship and I still think that was the right call.

Besides docs, I found that I learned the fastest from one-on-one code walkthroughs with experienced engineers. When I competed in ARML back before college, I had a coach who’d say something like “if you don’t understand the problem, grab the person next to you by the arm and get them to explain it”. This makes sense for obvious reasons: the choice was between wasting 5 minutes of someone else’s time (the explainer will often reveal their own misunderstandings in the process anyways) or be useless for the whole round.

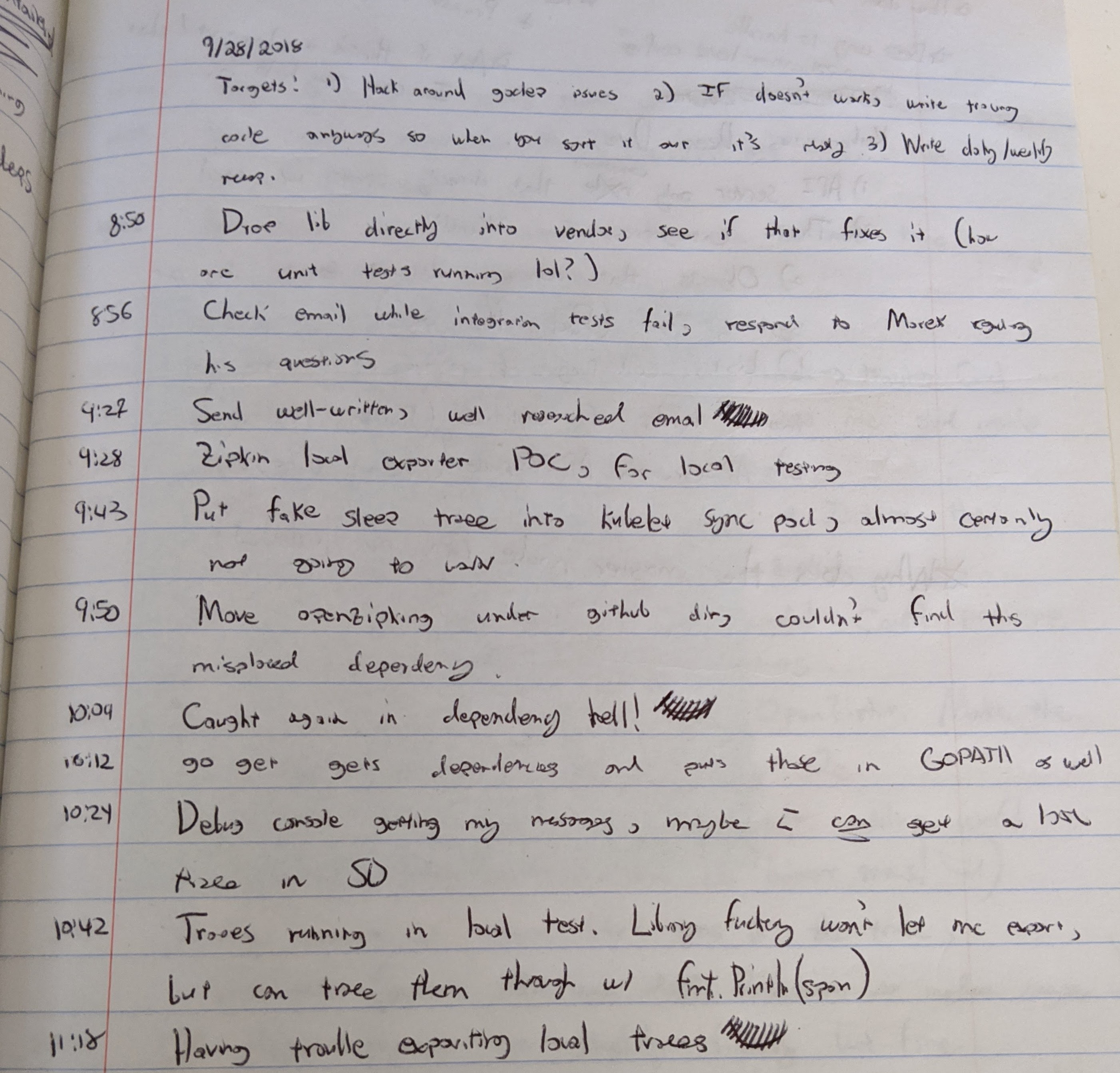

So, over the course of the week I would write things down that confused me in the codebase and schedule a 30-40 minute meeting with an engineer who could tolerate an intern for that long. I kept a painstaking technical log, the contents of which closely traced my mental descent. Littered with illegible scrawls, lines trailing into the margin and off the page, blood from where I’d gnawed my hands in aggravation. The level of detail became so neurotic at some point that I had to scale it back for the sake of productivity.

Another interesting thing (that should have been obvious in retrospect): going in, I had the expectation that engineers at a place like Google would have all the answers knocking around in their head. They don’t. They’re really good at knowing when they’re stuck and finding the right person to help them. The best engineers there have no ego about them. Walking up to another engineer with a question is the most natural thing in the world to them.

Contributing

My task was to add distributed tracing to Kubernetes. This was different in nature than, say, writing a new CSI driver, or fixing a scheduler bug. The task was an architectural change. There’s no single codepath to understand and fix- the goal was to make the whole system more understandable, to decompose a distributed operation into something that could be broken down and visualized. Even just defining the term “operation” in the Kubernetes context is harder than you might think.

Adding distributed tracing to a system isn’t actually so difficult in general. You identify the code paths that contain substantive work and wrap them with span creations and deletions. Work typically triggers other work which leads us to the concept of parent spans and children spans. We end up with a kind of hierarchy of work that ends up represented as a DAG of spans. The code ends up being instrumented with lots of little snippets like below:

|

|

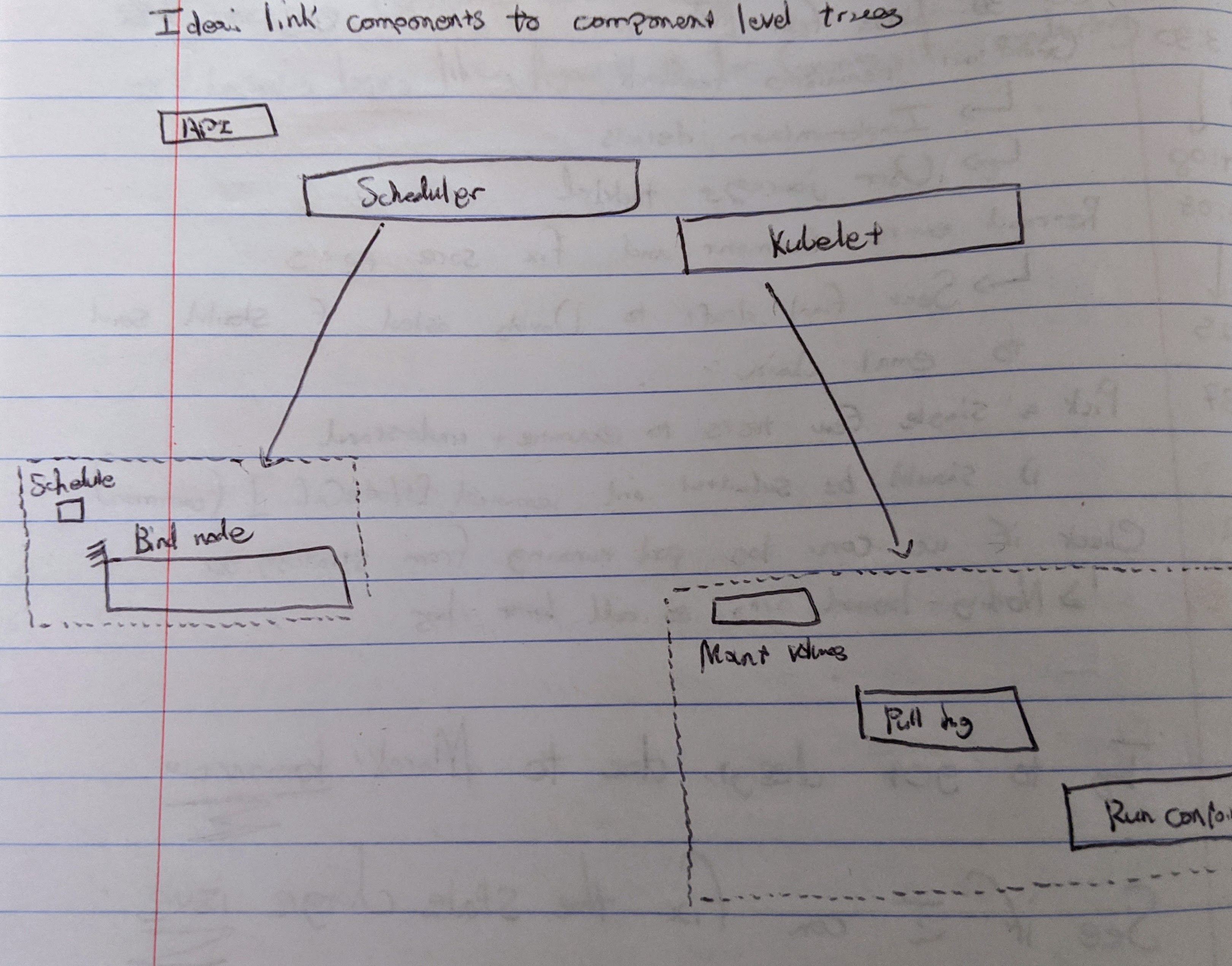

In Kubernetes, however, it’s not always so clear what should be held responsible for kicking off an operation. Components watch a state store for changes and react to those changes, but never explicitly tell each other what to do. Tracing also assumes that it’s obvious what a complete unit of work looks like from beginning to end (i.e. handling a request from receipt to response, rendering a single frame of a 3D scene), but in Kubernetes, this model breaks down. It’s not actually obvious when we want traces to begin and end.

Eventually I arrived at some early trace concepts as shown below and managed some basic demos. The project ended up as mostly high-level design work, culminating in a Kubernetes Enhancement Proposal (KEP) and some implementation for demo purposes. This project, which injects trace context into Kubernetes objects before admission, ended up getting merged into the kubernetes-sigs org. There were still some unanswered questions but lots of promise.

We could follow pod-startup across the api-server, scheduler, kubelet, and even into the container runtime, with little bars showing how long each step took. We could visualize pod startup latencies in Kubernetes to a degree of detail that had never been achieved before. The demos definitely got some stakeholders ooh’ing and ahhh’ing, but it takes more than flashy demos to get an architectural feature merged into a project like Kubernetes.

I won’t go further into the technical details on the work I did on adding distributed tracing to Kubernetes for now. First off, it’s a work in progress, and almost two years after the internship, it’s still under active development. Second off, the discussion warrants its own blog post to touch on the finer points, which are the most interesting points.

I’ll leave this by saying how grateful I am to David Ashpole for his patient guidance and how proud I am of what we got done that fall.